How Do Sand Dollars Move?

Sand dollars’ movement, like other Echinoderms, is always an interesting topic because, at first glance, they don’t have obvious limbs to do that. I remember when I was wondering myself, how they move forward, how they stay on the bottom during strong currents, or how they bury themselves in the sand. In this post, we’ll talk all about that. However, let’s start with a quick answer:

Sand dollars move horizontally using their spines located on the bottom of their body. They use them in a rowing motion, and move in a linear path, only being able to go forward. Four types of sand dollars’ movements are rotation, progression, burying, and righting movements.

However, this certainly doesn’t tell the whole story and in this post, I’ll explain more about how sand dollars move, the types of their movements, how they are able to stay on the bottom, and why they move. Read on!

Sand dollar movement

Sand dollars are living animals that are part of the phylum Echinodermata which in Greek means “spiny skin”. The movement of these marine animals is accompanied by structures including arms, tube feet, spines, and the body wall. However, the way these marine creatures move may differ and depend on the class. In a sand dollar case (Echinoids), just like its close relative, sea urchin, sand dollar uses its spines located on the bottom of its body to move around the seafloor. It uses them in a rowing motion to move through the sediment front-end forward. However, unlike sea urchins, sand dollars’ spines are non-harmful.

To describe the different movements of the sand dollar in more detail, I’ll divide it into four types: rotation, progression, sand burying, and righting movements.

The rotation and progression movements

When the sand dollar wants to change the direction, for example, because met an obstacle, it uses the rotation movement. In rotation, the sand dollar usually turns by using its mouth as a center in either clockwise or counterclockwise direction.

The progression movement usually is combined with rotation. Once the sand dollar picks the direction, it starts moving on a linear path. The progression is very slow with an average rate of 13.7 mm (0.54 inches) per minute. The highest progression rates that have been observed vary by research and species. H. L. Clark has recorded rates for two different species of 20 – 85 mm (0.78 – 3.35 inch) per minute. G. H. Parker recorded the highest progression rate of 18 mm (0.7 inches) per minute.

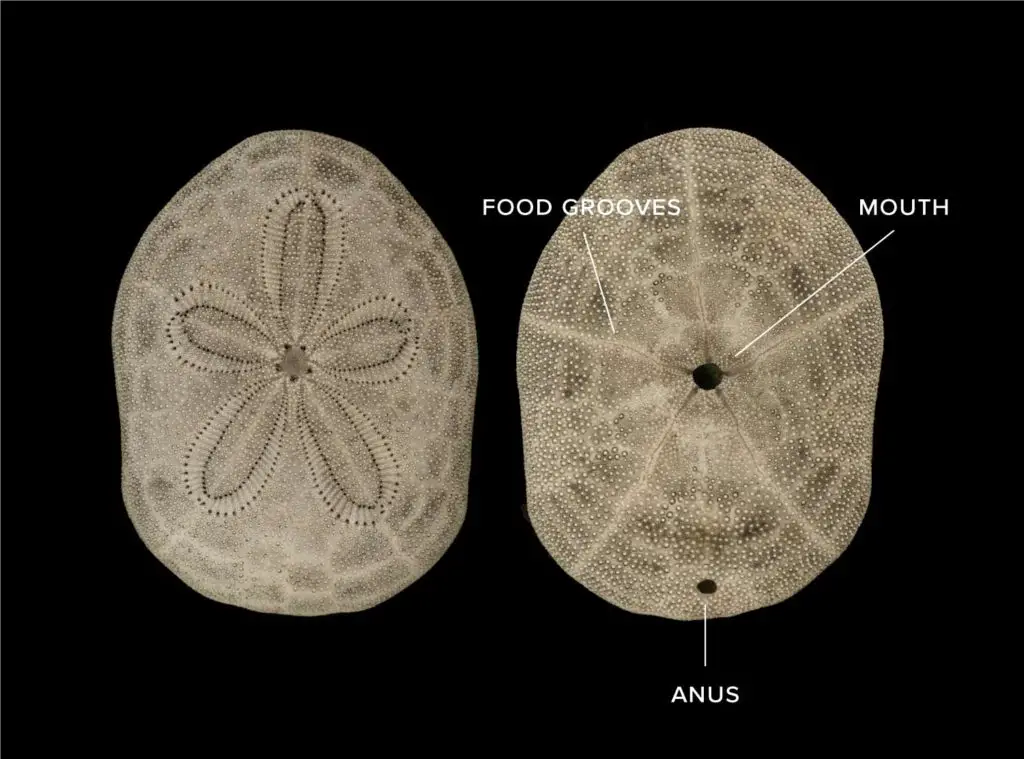

Sand dollar moves according to its structural axis. The axis goes in a straight line through its body. It starts from the anus, which is located on the bottom tip of its body, extends through sand dollar’s center where the mouth is situated, and ends on the other side of a sand dollar’s shell.

Sand dollar moves in this line of motion, where the edge of its skeleton opposite to the anus, is always carried forward. This marine creature is able to move only within this line and is not able to go backwards so if it meets any obstacles, it will first rotate, and then progress forward.

Sand burying and righting movements

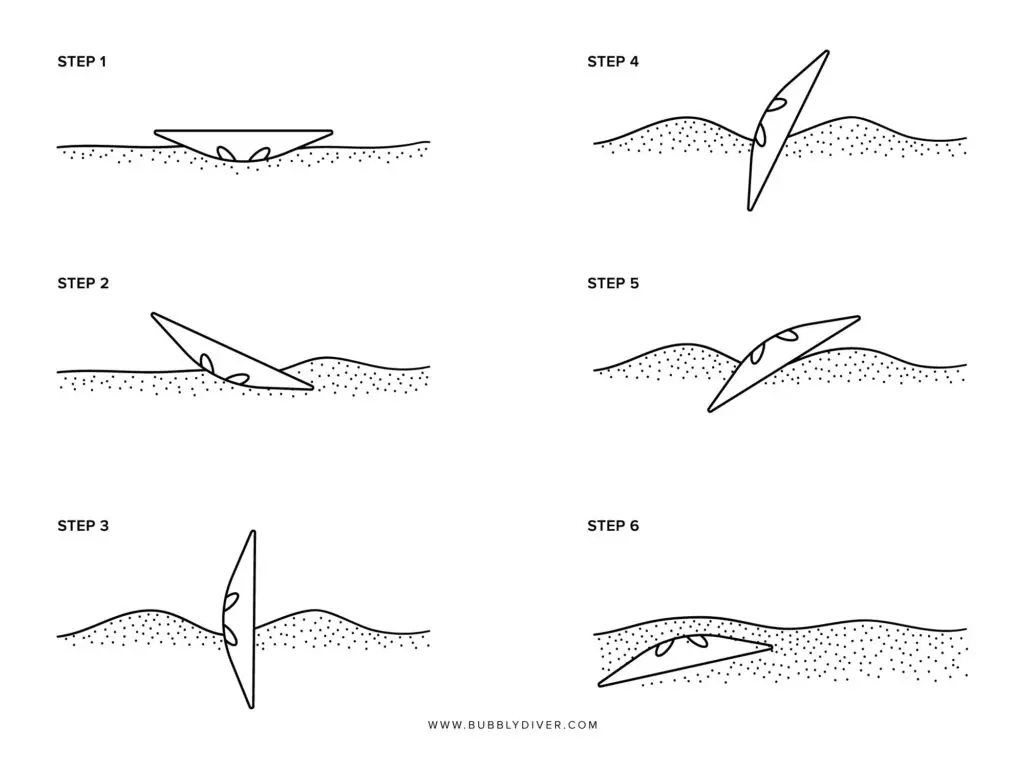

In order to protect itself, the sand dollar buries itself in the sand so it becomes invisible to its predators. It also uses this technique to avoid being washed out of the sand and thrown on the beach by strong currents and tides. It’s mostly found in the horizontal position with the oral side down. Again, it uses its spines to disappear in the sandy bottom of the ocean.

However, if a sand dollar is turned oral side up, a very interesting movement happens. First, it uses its spines to bring the edge of its skeleton under the sand. Next, it works on flipping its body to a vertical position. Once this is achieved, the sand dollar instead of dropping down with its oral side up, it buries itself forward until it’s fully covered by sand. This way it comes to its natural position and this process can take several hours.

What’s interesting is that the first steps, when the sand dollar is flipping horizontally, take much more time than the next steps, because the spines on top of the sand dollar’s body are less developed and active.

Why do they move?

Like all animals on the planet, including humans, sand dollars move to feed themselves. They mostly eat detritus (dead particulate organic material), planktons, crustacean larvae, and debris from the seafloor. They grind their food up with the teeth inside of them. If you’d like to read more about what’s inside a sand dollar, I wrote a separate blog post about it.

Sand dollars move also in order to protect themselves. As I mentioned above, they bury themselves in the sand and hide from predators and currents. They may be buried about 7 cm or more (3 inches) down.

How do sand dollas are able to stay on the bottom?

The sand dollars’ most common cause of death are not necessary their predators but strong current and tides. In order to stay on the bottom, as I already mentioned, sand dollars bury themselves in the sand. They also use their holes known as lunules to let water pass through so they’re not blown away by the current. If they’re unable to stay on the ground, this normally means the end of their 10-year life cycle.

What’s interesting about young sand dollars is that scientists noticed they pick small grains of magnetite from the sand and store them in chambers of their gut called diverticula. They use diverticula as weight belts, and exactly like divers use theirs, they help them to stay on the bottom. This iron-rich mineral weighs young sand dollars down, keeping them grounded until they grow bigger and heavier so they’re not washed away.

If they’re washed away, they will end up on tropical beaches and get bleached, which is how a sand dollar is made. The silvery look they get looks a lot like an old silver dollar, which is why we call them sand dollars.

Sources

- Maria Byrne, Timothy D O’Hara “Australian Echinoderms: Biology, Ecology and Evolution.” 2017, CSIRO.

- Parker, G. H. “Locomotion and Righting Movements in Echinoderms, Especially in Echinarachnius.” The American Journal of Psychology, vol. 39, no. 1/4, University of Illinois Press, 1927, pp. 167–80, https://doi.org/10.2307/1415410.

You may also like:

Welcome to Bubbly Diver!

I’m glad to see you here. This blog is created for all marine creature lovers by a bubbly diver - me, Dori :)